Alasdair Gray

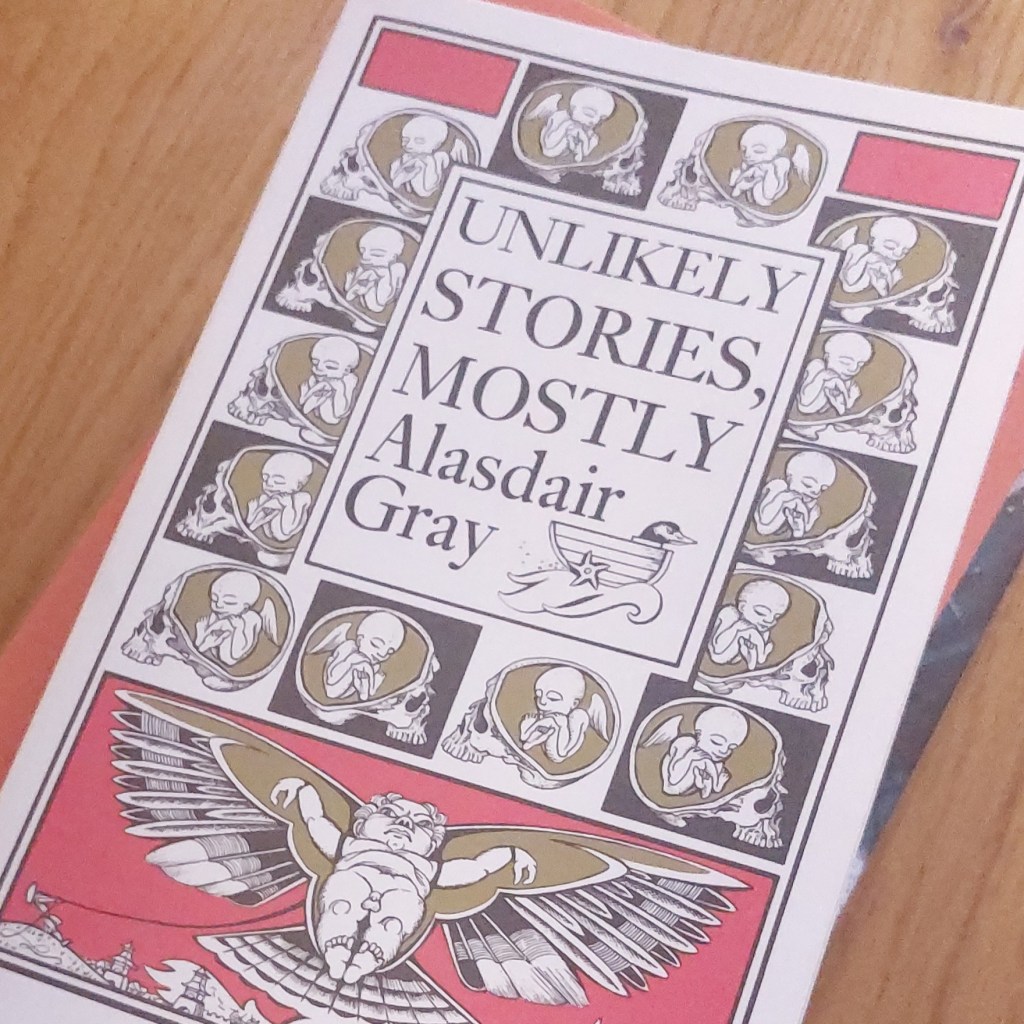

This collection of stories is striking, mostly, because of the illustrations, the typography and the postmodern style of the author. If it is not already obvious, it helps contextually to bear in mind that Alasdair Gray was an artist and political thinker, as much as he was a writer of fiction.

There is a postscript to these stories, begun by the author and taken up by a critic, which give analysis and background, as if the author is aware that his work will be met with confusion and criticism and is getting ahead of the game. I would advise readers to refer to this postscript as they progress, especially during the second half of the book.

That said, there are some stories in this book that do not require any explanation, and indeed the collection opens with ‘The Star’, a beautiful and touching story told through the eyes of a particularly imaginative and thoughtful child, as the author likely once was. There are also fable-like and pourquoi stories that are funny and entertaining, in which Gray demonstrates the breadth of his talent as a writer.

Mostly, though, this book is postmodernist, with some comparing Gray to Franz Kafka. Some of these later stories made feel confused and wondering if there was a point to them, or if they were just an experiment with visual art. The virtually impenetrable typography of ‘Sir Thomas’s Logopandocy’ is an example of this. At other times I was unsettled, particularly with the illustrations and at other times, such as in the ‘Axletree’ stories, it was easy to see the allegorical political writing coming through, but with no real characterisation. A couple of these stories also seemed to parody seventeenth century novels, which I found to be reminiscent of Laurence Strerne’s ‘The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman’ (1767), in that they used an enormous number of words to say very little. Although the narrative, combined with the illustrations and typography created something that made me feel uncomfortable and confused, I pushed on, feeling that my intellect and love of literature were being tested, vaguely aware that I was being made to look a fool. Something in the writing, though, made me yearn to understand, even if it was to understand my own stupidity, and keep on reading with the type of morbid curiosity that means you can’t look away, even when trudging through ‘M. Pollard’s Prometheus’.

Gray is the second giant of Scottish literature that I have tackled this year, the other having been Walter Scott. For both, I chose to begin with short fiction in order to get a taste of their work. After reading Scott’s ‘Supernatural Short Stories’ (1818-1830) (see my review), I found myself certain to go and read his novels. With Gray, my target was to go on to ‘Lanark’ (1981), but now I am not so sure.

The themes coming through from these stories were predominantly those of anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism, as well as the ease of manipulation of the masses, (yes, I know that includes me). In relation to this last theme, in this respect Gray shares similarities to Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein (1818), combined with the creature creation that runs throughout Gray’s work. Gray himself was a vocal supporter of socialism and Scottish independence, with which I sympathise, and of course I recognise his talent as a visual artist that was able to cross over into literature, but if I am to commit to ‘Lanark’ I need to know that there is a plot and that there are characters that I can empathise with. I’ve read all the reviews . . . If I really want an answer, there’s only one other way to find out I suppose.

Leave a comment