Discussing Caledonian Antisyzygy

Syzygy, a wonderful sounding word with its origins in Greek, means the alignment of two things. Antisyzygy, therefore, is opposed to the alignment of two things.

Caledonian Antisyzygy, as with all things Scottish, is a little more complex.

The O.E.D. defines it as:

‘The coexistence of contrasting or contrary characteristics, ideas or principles, considered or represented as a distinguishing feature of Scottish people and represented esp. in literature’.

The entry goes on to say that the term was coined by G.G.Smith in his book Scottish Literature (1919) and was popularised by the poet Hugh MacDairmid around 1931. A further Wiktionary definition states that Caledonian Antisyzygy is typical of the Scottish psyche and literature.

My favourite example, and probably the most famous example, of duality in literature is Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886). The book is so well known that the term ‘Jekyll and Hyde’, when referring to the sudden changing, or hidden side of a person’s character, is still in everyday usage a century and a half on. It is often seen as symbolic of the contrast between the poverty of Edinburgh’s Old Town and affluence of the New Town, but a more apt example of Caledonian Syzygy is Kidnapped, published in the same year, which was RLS’s analogy of the cultural, religious, political and geographical polarities existing in Scotland.

In Jekyll and Hyde, these opposing forces exist in one person and lead to destruction, while in Kidnapped they are represented by David and Alan, who are obliged to work together for the sake of mutual benefit.

RLS was influenced to write about The Appin Murder Case, which is central to the plot of Kidnapped, by Walter Scott’s Rob Roy (1817). Scott’s themes (as discussed in my review of his Supernatural Short Stories) include an underlying desire that Scots with opposing beliefs should bury the hatchet and accept the status quo (i.e., the union), rather than RLS’s message that opposites should reach a compromise that is satisfactory to both.

An interpretation of Caledonian Antisyzygy could be that it is an internal form of institutionalisation that has been bred through design and built up over centuries through indoctrination. The deliberate erosion of language and culture and the mantra of church and education that Scots should be ashamed of their past and their languages, as Lewis Grassic Gibbon writes in Sunset Song (1932):

“Rob was just saying what a shame it was that folk should be ashamed nowadays to speak Scotch […]”.

More of a flash point than Scots, though, is Gaelic. The fact that I am frequently asked about my decision to spell my name in the language in which it originates, i.e., not the anglicised version, attracts a lot of questions. I am asked to explain myself, simply for wanting to pay tribute to the rich language and story-telling culture of my ancestors. I think that says a lot about us as a nation. The self-loathing and abhorrence of our own ancestry is so ingrained we are barely aware of it. I was once on a train with a guy who became angry about the bilingual English/Gaelic platform signs. ‘Get rid of that language’ he says; his name: Munro, a name with its roots in Irish Gaelic. What becomes really confounding is when the unspoken religious question is considered. A large percentage of modern Gaelic speakers are Presbyterian. Although, in a country that gets its knickers in a knot about religion, it seems that very few of us go to church. There are also those who say that the languages (Scots and Gaelic) are dead, that English is the language of the world. I’m not sure that speakers of other languages would agree to give up their native tongues.

There are also accusations that advocates of Scots and Gaelic are somehow anti-English, but it is possible to appreciate, enjoy, and even speak, more than one language. Not only is English significant in terms of its place as an international business language, but English is also a beautiful hybrid of ancient and old languages with connections to Latin, Old German and Old French (among others) with the versatility to say things in many ways and providing the tools to create the English literature that has been enormously influential to worldwide literature. I am a student of English Literature that has loved to read and write in English since early childhood, my bookshelves are packed with classic and modern English literature, but I also love the history of storytelling, which, in Scotland, means an enthusiasm for the traditions of Celtic, Scottish and Norse myth. On a wider scale I am passionate about etymology, the theory of literature and the evolution and development of language, and English literature is central to all of that.

In Gibbon’s Sunset Song, another characteristic of Caledonian Antisyzygy is at play: a yearning for past ways, while simultaneously harbouring an inner feeling of inferiority caused by an embarrassment of the past. To hear people claiming to be both British and Scottish before going on to sing Flower of Scotland at a sporting event is common, and to hear folk make the Gaelic toast ‘Slàinte mhath’ before bemoaning the cost of Gaelic signage also occurs frequently. These contradictions and hypocrisies are usually involuntary and can provoke anger if they are brought to attention. Sadly, they are the symptoms of a psychologically damaged nation that thinks nothing of treating the sanctity of the welfare state with apathy one minute before violently defending the sugar content of its favourite soft drink the next. This polarity is more than illustrated in light of two facts: firstly, Scotland has the proud distinction of being the only country in the world where Coca Cola is not the best-selling soft drink; secondly, Scotland is the only country ever to reject its own independence at the ballot box.

In his short story The Two Drovers (1827) Walter Scott writes that a Scottish person’s sense of self-esteem would be viewed as ridiculous elsewhere, and should be hidden away:

“The pride of birth, therefore, was like the miser’s treasure: the secret subject of his contemplation, but never exhibited to strangers […]”

But, as further proof of the point, Scott himself uses Scottish dialects and themes to great effect, treating them with dignity and respect, within his work.

In the Northeast of Scotland (where the demise of our own favourite soft drink, Moray Cup, is greatly lamented), there is an issue that is likely to attract far more passionate debate than anything political, and that is when discussing the correct name, texture, baker of origin and serving method of a certain flat pastry item called a buttery (or rowie)!

A Scotland-wide divide though, becomes apparent in the chip shop. It is not the central belt debate over whether chip suppers should be seasoned with salt and vinegar or salt and sauce. The big divide, one that reaches into the misty past, is whether or not the chipper sells reed puddin suppers. The fact that these are rarely available in the south of Scotland says a lot about our historical, cultural and geographical differences.

But now we’re talking about sausages and not syzygy.

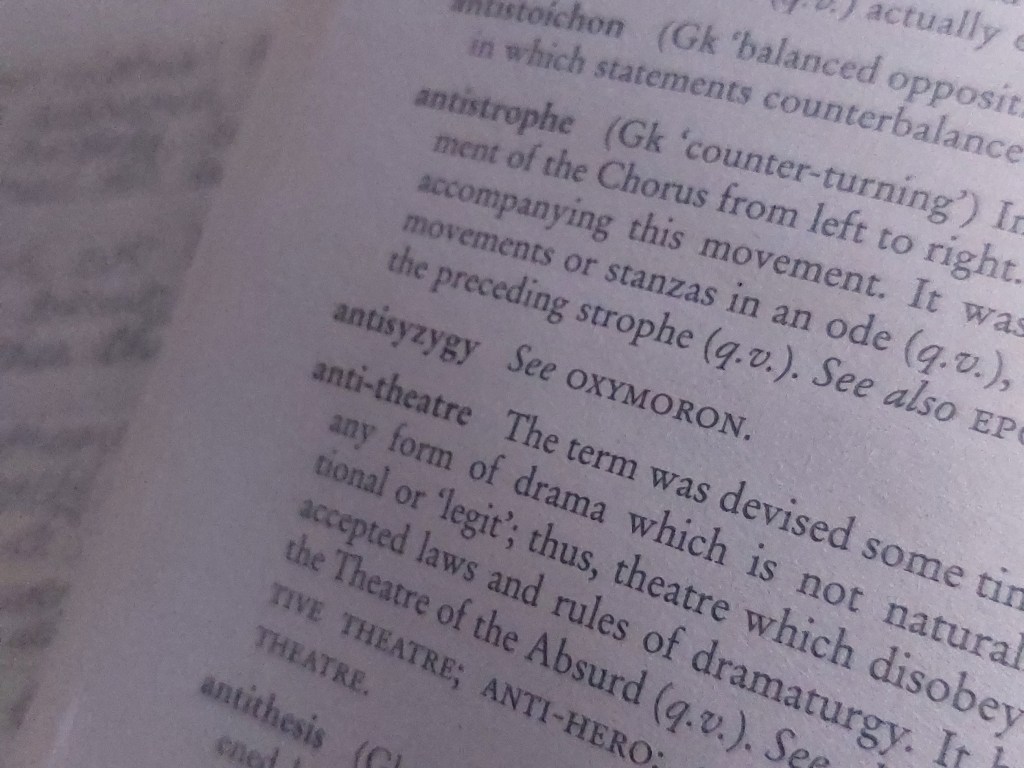

A final note on definitions of antisyzygy. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms (Fourth Edition, 1999) entry says See Oxymoron, the Greek derivation of which is ‘Pointedly Foolish’.

Leave a comment