by Victor Hugo

I only got round to reading this last year, at the age of fifty-two. Part of me wishes I had read it earlier, but then, on the other hand, there are many books that I wish I could read again for the first time so I’m glad I saved this one till later.

This is an analysis rather than a review, so I will be discussing plot.

This book opens gently with parable-like descriptions of the life of Monsignor Myriel, which are soothing and cathartic. As you heft the fifteen hundred pages of this novel in your hands, and you are introduced to Jean Valjean, you sense that you are at the beginning of a long and special journey.

Hugo indicates that he will use experience to bring about change in his characters. He spends a lot of time digressing from the main plot to discuss French culture, socialist values and the importance of the history of the French Revolution, but these asides blend well with the narrative. Personally, I needed to know more, and read a short history of the revolution, a complex period of history. This novel contains for instance, a highly detailed description of the battle of Waterloo. Hugo (a Royalist as a young man who became a Republican) claims Waterloo as a victory for the French, in much the same way as the Jacobites (and subsequent generations of Highland people) claimed a moral victory at Culloden (see Bluebell Souls) – citing misfortune (and poor leadership in Culloden’s case) and the bravery of starving and out-numbered men. Hugo stresses the importance of this pivotal moment in European History, which was an important advancement towards the social equality we have today.

Aside from this, Les Misérables is an in-depth study of the human condition. Valjean is a criminal in the eyes of the law, and indeed himself. He attempts to repay the trust given to him by trying to do good. His ardent and religious application of this has devastating consequences, though. Hugo’s message here is that the law and religion, certainly in the mid-nineteenth century, lacked compassion. In the factory passages, Valjean’s generosity is criticised, (Who does he think he is?) and the petty jealousies of people that contribute to the tragedy when they see others getting on or finding happiness – is evidence of the incomprehensible cruelty that human beings can inflict upon one another.

In Javert we have a character who is a machine as relentless as a The Terminator, seeking to uphold the law at all costs. When he sees evidence that the law is not always just, he cannot come to terms with the realisation that doing the right thing may mean turning a blind eye rather than blindly pursuing. In the course of the novel, characters are often tested with these types of moral questions: What would you do if another is accused in your place? How far would you go to provide for your child?

Hugo also presents us with the Thénardiers, Monsieur and Madame supposedly symbolic of the middle classes, remain maliciously exploitative of those in their employ, including their own children, throughout the book. Gavroche also remains unchanged; he is brave, devoted and happy throughout, also symbolic of the pliable nature of the general public. His sister Eponine, prostituted by her parents, is unloved and tortured by her jealousy of Cossette, and she alone amongst the Thénardiers is transformed when she demonstrates the ultimate sacrifice of unconditional love. She is an example of a rare type of human being. This novel, again invoking the human element, warns us that we should not take loved ones for granted and that we should let them know how we feel about them.

With a little research about the author, it is evident that Marius is very much autobiographical – a royalist turned republican that was at odds with his father. Hugo was a democratic socialist and pro-European well ahead of his time and he sought to highlight prejudice and the lack of passion for ‘The Wretched’. I admire his bravery in this, and his abhorrence of the violence that came with the revolution. For his opposition to Napolean III he spent many years in exile and wrote Les Misérables in exile on the Island of Guernsey. (He had also been expelled from Jersey for supporting criticism of Queen Victoria). I think that knowledge of these facts, and the passions of Hugo, add weight to the novel.

Les Misérables, as can be attested to with the popularity of the stage musical, is a hugely entertaining book. It is full of tension as Jean Valjean is hunted and hope as Fantine struggles to build a life. There is action and heartbreak.

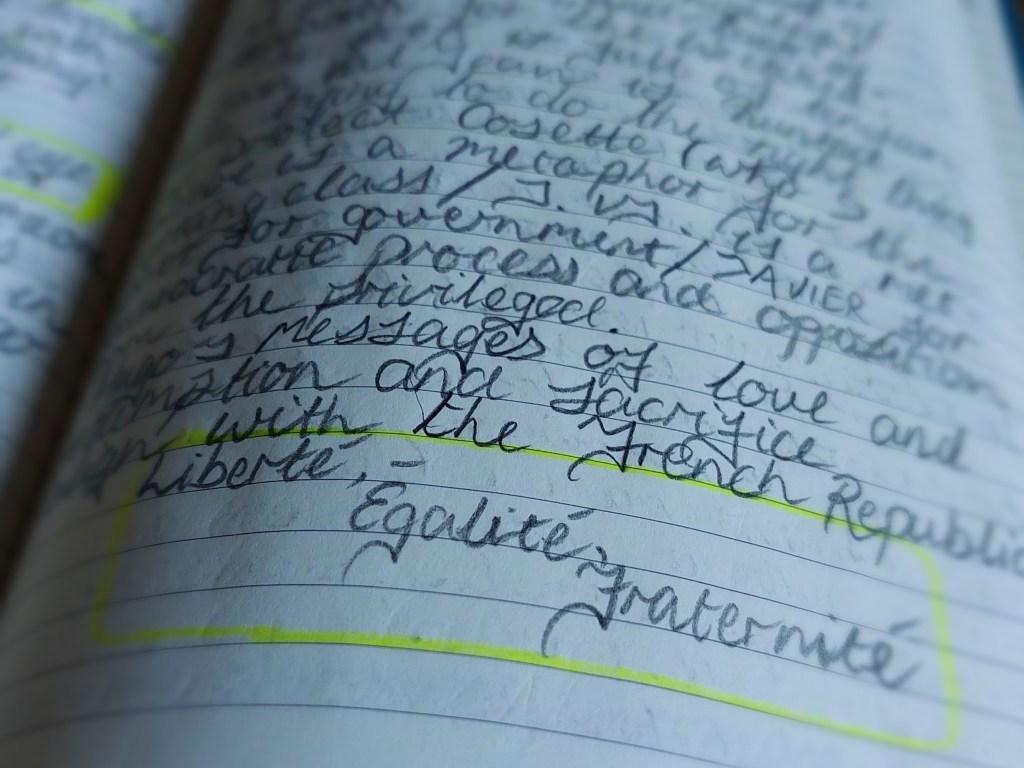

Hugo delivers this fantastic journey, and his messages of love, redemption and sacrifice land as squarely as the French motto:

“Liberté, égalité, fraternité”.

At the end of this long journey with Jean Valjean I felt that I had become richer for sharing it.

Leave a comment